UNDERSTANDING THE HUMAN RIGHTS

OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES

| Navigation | |

|---|---|

|

Main Index Part 2 Part 3 Annexes |

|

| PART 1:

UNDERSTANDING THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES |

|---|

| |

|

The background information and exercises contained in this chapter will prepare participants to use this manual effectively by developing a fundamental understanding of:

People with disabilities have the same rights as all other people. However, for a number of reasons they often face social, legal, and practical barriers in claiming their human rights on an equal basis with others. These reasons commonly stem from misperceptions and negative attitudes toward disability.

| Exercise 1: The Impact of Myths and Stereotypes about Persons with Disabilities |

| Objective: | To share lived experiences with discrimination based on myths and stereotypes and begin thinking about their impact on human rights |

| Time: | 45 minutes |

| Materials: | Optional: Copies of "Common Myths and Stereotypes about People with Disabilities" |

1. Introduce:

Explain that discrimination is often based on mistaken ideas and stereotypes that one

group holds about another. This exercise will examine the impact of these myths and stereotypes on

the lives of people with disabilities.

2. Brainstorm/Analyze:

Divide participants into small discussion groups and ask them to develop a list of myths and

stereotypes about people with disabilities. Ask each group to discuss these questions:

3. Report/Discuss:

Ask a spokesperson from each group to summarize their conclusions and discuss their findings.

Discuss these or similar questions:

Variation:

Conclude the exercise by distributing the handout "Myths and Stereotypes about People with Disabilities."

Compare this list with that generated by participants and ask questions like these:

Myths and Stereotypes about People with Disabilities

People with disabilities -

|

To provide a foundation for examining the human rights of people with disabilities, this chapter begins by examining fundamental human rights principles and the general human rights framework. It then looks at human rights in the context of disability.

What are Human Rights?Human rights are based on human needs. They assert that every person is equally entitled not only to life, but to a life of dignity. Human rights also recognize that certain basic conditions and resources are necessary to live a dignified life.

Human rights have essential qualities that make them different from other ideas or principles. Human Rights are:Universal: human rights apply to every person in the world, regardless of their race, color, sex, ethnic or social origin, religion, language, nationality, age, sexual orientation, disability, or other status. They apply equally and without discrimination to each and every person. The only requirement for having human rights is to be human.

Inherent: human rights are a natural part of who you are. The text of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) begins "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights."

Inalienable: human rights automatically belong to each human being. They do not need to be given to people by their government or any other authority, nor can they be taken away. Nobody can tell you that you do not have these rights. Even if your rights are violated or you are prevented from claiming your human rights, you are still entitled to these rights.

Human rights relate to one another in important ways. They are:

Indivisible: human rights cannot be separated from each other;

Interdependent: human rights cannot be fully realized without each other;

Interrelated: human rights affect each other.

In simple terms, human rights all work together and we need them all. For example, a person's ability to exercise the right to vote can be affected by the rights to education, freedom of opinion and information, or even an adequate standard of living. A government cannot pick and choose which rights it will uphold for the people who live in that country. Each right is necessary and affects the others.

Human rights are outlined in a variety of international human rights documents, (sometimes called "instruments") some of which are legally binding and others that provide important guidelines but are not considered international law. This section looks at the overall human rights framework.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the United Nations in 1948. Many other documents have since been developed to provide more specific details about human rights; however, they are all based on the fundamental human rights principles laid out in the UDHR. The full text of the UDHR can be found in Annex 1, p. 244. Below is the official abbreviated version of the UDHR, which lists the key concept of each article in the Declaration.

| The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (Official Abbreviated Version) |

|

| Article 1 | Right to Equality |

| Article 2 | Freedom from Discrimination |

| Article 3 | Right to Life, Liberty, and Personal Security |

| Article 4 | Freedom from Slavery |

| Article 5 | Freedom from Torture and Degrading Treatment |

| Article 6 | Right to Recognition as a Person before the Law |

| Article 7 | Right to Equality before the Law |

| Article 8 | Right to Remedy by Competent Tribunal |

| Article 9 | Freedom from Arbitrary Arrest and Exile |

| Article 10 | Right to Fair Public Hearing |

| Article 11 | Right to be Considered Innocent until Proven Guilty |

| Article 12 | Freedom from Interference with Privacy, Family, Home, and Correspondence |

| Article 13 | Right to Free Movement in and out of the Country |

| Article 14 | Right to Asylum in other Countries from Persecution |

| Article 15 | Right to a Nationality and the Freedom to Change It |

| Article 16 | Right to Marriage and Family |

| Article 17 | Right to Own Property |

| Article 18 | Freedom of Belief and Religion |

| Article 19 | Freedom of Opinion and Information |

| Article 20 | Right of Peaceful Assembly and Association |

| Article 21 | Right to Participate in Government and in Free Elections |

| Article 22 | Right to Social Security |

| Article 23 | Right to Desirable Work and to Join Trade Unions |

| Article 24 | Right to Rest and Leisure |

| Article 25 | Right to Adequate Living Standard |

| Article 26 | Right to Education |

| Article 27 | Right to Participate in the Cultural Life of Community |

| Article 28 | Right to a Social Order that Articulates this Document |

| Article 29 | Community Duties Essential to Free and Full Development |

| Article 30 | Freedom from State or Personal Interference in the above Rights |

| Exercise 2: The Interdependence of Rights |

| Objective: | To examine the fundamental human rights contained in the UDHR and raise awareness of how these rights relate to each other |

| Time: | 45 minutes |

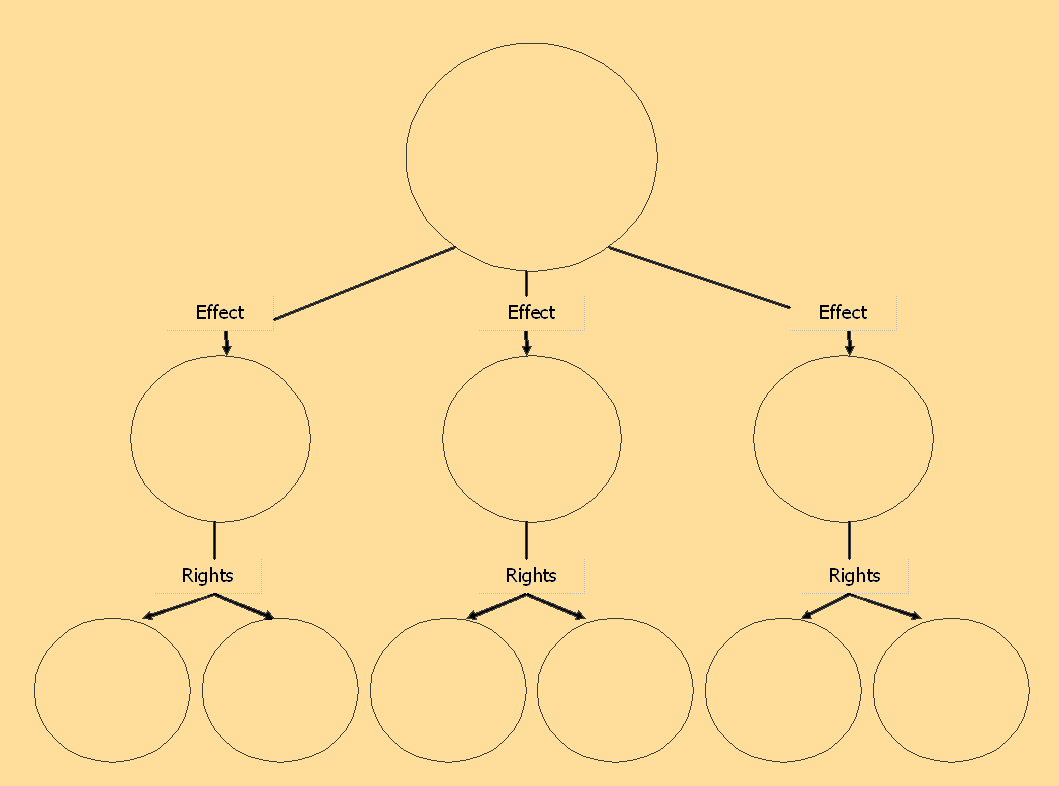

| Materials: | Chart paper and markers or blackboard and chalk Copies of Effects Cascade for each small group Copies of the simplified version of the UDHR |

1. Explain/Illustrate:

Introduce the activity by observing that human rights are based on human needs and

that everyone is entitled to and needs all their human rights. Explain that this activity helps to

illustrate how rights are indivisible, interdependent, and interrelated and the far-reaching effects

when just one right is denied.

Demonstrate how the "Effects Cascade" works:

Alternative: Ask each group to write the number of the UDHR article for each right mentioned in the cascade (e.g., "Inability to get a good job": Article 25, Right to Adequate Living Standard; Article 23, Right to Desirable Work).

2. Complete:

Divide participants into small groups of 2-4 and give each a copy of the Effects Cascade. Ask

each group to write a human right in the center of their chart. Encourage groups to choose

a variety of different rights. Ask them to consider what effects result when a person with

disabilities - or anyone - is denied this right.

Note to Facilitator: Participants may think of more than three effects, but encourage them to choose the three most far-reaching effects.

3. Discuss:

Ask a spokesperson from each group to present its chart. Discuss the results.

2. International Human Rights Conventions

A convention (also known as a treaty) is a written agreement between States. It is typically drafted by a working group appointed by the UN General Assembly. Once the convention is drafted, it goes to the UN General Assembly for adoption. The next step is for countries to sign and ratify it. By signing a convention, a country is making a commitment to follow the principles in the convention and to begin the ratification process, but the convention is not legally binding on a country until it is ratified. Ratification is a process that takes place in each country, whereby the legislative body of the government takes the necessary steps to officially accept the convention as part of its national legal structure. Once a country signs and ratifies a convention, it becomes a State Party to that convention, meaning it has a legal obligation to uphold the rights the convention defines. Each convention must be ratified by a particular number of countries before it enters into force and becomes part of international law.

In the last sixty years, several human rights conventions have been developed that elaborate on the human rights contained in the UDHR. Nine of these instruments are considered "core" human rights conventions: they cover a major human rights issue and have a treaty-monitoring body that assesses and enforces how a State meets it obligations to that treaty.

Two of these conventions are called covenants and address broad human rights issues:

The two Covenants and the UDHR combine to create a trio of documents known as the International Bill of Rights.

An additional seven UN human rights conventions address either thematic issues or particular populations.3

| THE HUMAN RIGHTS FRAMEWORK |

||

| INSTRUMENT | ENTERED INTO FORCE |

|

| Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) | Not Applicable | |

| International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) | 1976 | |

| International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) | 1976 | |

| Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) | 1965 | |

| Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) |

1979 | |

| Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) |

1984 | |

| Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) | 1989 | |

| Convention on Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families |

1990 | |

| International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance |

* | |

| Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) | * | |

| *Not yet entered into force as of September 2007 | ||

| These nine core human rights conventions form an interdependent human rights framework. It is useful to be familiar with them and to know which of these Conventions your country has ratified and is therefore legally obligated to enforce and implement. |

||

3. Regional Human Rights Conventions

In addition to the UN human rights framework, which applies globally, some regional institutions

have developed human rights instruments specifically for the countries in their region. These

include -

Governments:

Governments are the primary actors responsible for ensuring people's human rights.

Governments must ensure that political and legal systems are structured to uphold human

rights through laws, policies, and programs, and that they operate effectively. In some cases,

international conventions and treaties are the main source of a State's legal obligations with

respect to human rights. However, in many countries, national constitutions, bills of rights, and

legal frameworks have been developed or amended specifically to reflect universal human

rights principles and standards in international law, providing a double layer of protection and

reinforcement of these principles on the national level.

Governments have a legal obligation to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights.

|

Respecting, Protecting, and Fulfilling Human Rights

Respect: The obligation to "respect" human rights means that States must not interfere with the exercise and enjoyment of the rights of people with disabilities. They must refrain from any action that violates human rights. They must also eliminate laws, policies, and practices that are contrary to human rights. Protect: The obligation to "protect" human rights means that the State is required to protect everyone, including people with disabilities, against abuses by non-State actors, such as individuals, businesses, institutions, or other private organizations. Fulfill: The obligation to "fulfill" human rights means that States must take positive action to ensure that everyone, including people with disabilities can exercise their human rights. They must adopt laws and policies that promote human rights. They must develop programs and take other measures to implement these rights. They must allocate the necessary resources to enforce laws and fund programmatic efforts. |

Although only governments have the official legal responsibility for respecting, protecting, and fulfilling human rights under international human rights law, human rights are not their exclusive responsibilities. Human rights are far more than legal requirements. They represent a moral code of conduct designed to promote understanding, equality, tolerance, fairness, and many other features essential to just and peaceful societies. Regardless of what behaviors may or may not be legally enforceable, a variety of actors, including individuals, groups, and institutions within society, also play important roles in the promotion and implementation of human rights.

Individuals:

Each person must know and understand their human rights in order to be able to claim them,

defend them, and hold themselves, other people, their governments, and societies accountable

for the actions that affect them. Because human rights are common to all people, even an effort

by a single individual to assert his or her human rights represents an important initiative on

behalf of every person. Likewise, actions of an individual that violate somebody else's human

rights represent a threat to everyone's human rights.

Groups:

Social and cultural behavior has a profound effect on the ability of people to enjoy their human

rights. The collective actions of groups - from families to entire societies - play a role in

human rights. For instance, if parents decide that only male children will be allowed to go to

school, they are effectively preventing their female children from claiming their human right

to an education. If broad cultural values result in persons from racial minorities experiencing

discrimination when they seek housing or public services, society itself is contributing to the

violation of the human right to an adequate standard of living. On the positive side, groups that

speak out against human rights violations and work to change harmful attitudes, policies or laws

can be very effective advocates for human rights.

The Private Sector:

Members of society interact with the private sector every day, especially in countries with free-

market economies. Private sector actors include people and entities of every kind: employers,

providers of goods and services, entertainers, and builders of houses, banks and even

government buildings. People depend on the private sector for many things. While private

sector actors are often required to adhere to certain laws and standards that uphold human

rights, it is impossible for governments to oversee every aspect of how the private sector

operates. Businesses, organizations, and other private sector players must make their own

commitment to ensuring that their practices do not violate people's human rights but, in fact,

support and promote them.

UN CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES

Persons with disabilities have long fought to have their human rights formally recognized in human rights law. In 2006 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the first convention that specifically addresses the human rights of people with disabilities. The CRPD is the first global convention addressing disability.

From the first meeting to draft the CRPD, members of the global disability rights movement insisted that people with disabilities be included in deciding what the convention should say.

The disability community was able to exercise a greater level of participation and influence in the drafting of the CRPD than any other specific group has ever been able to achieve in a UN human rights treaty process. As a result, the CRPD covers the full spectrum of human rights of persons with disabilities and takes much stronger positions than it would have if governments alone had drafted it. In addition, disability organizations, individuals with disabilities, governments, and the United Nations forged important relationships during this drafting process.

Now that the human rights of persons with disabilities have been recognized in international law through the CRPD, the next step is for persons with disabilities in all countries to continue to advocate and work with their governments to ensure that the Convention is ratified and implemented. Every person who advocates for their rights under the CRPD becomes an important member of the global disability rights movement!

General Principles in the CRPD

One important feature of the CRPD is the inclusion of an article that sets forth general principles. The drafters of the CRPD wanted the Convention to recognize a core set of concepts that underlie disability rights issues and are of particular importance in the disability context. They believed that it was crucial to identify these explicitly at the beginning of the text to ensure that all of the rights expressed in the Convention are interpreted through the lens of these particular principles.

|

CRPD Article 3: General Principles

The principles of the present Convention shall be:

|

Nearly all human rights conventions begin by recognizing respect for the human dignity and the inherent equality of all persons as the basis for human rights and fundamental freedoms. The CRPD General Principles include a number of other concepts that are particularly important to persons with disabilities, such as, non-discrimination, equality of opportunity, and respect for difference. Notably, the CRPD General Principles also stress the concepts of autonomy, independence, participation, and inclusion in society as essential to ensuring that the rights of persons with disabilities are respected, protected, and fulfilled. Although these concepts are certainly implicit in the substance of other core human rights conventions (e.g., in relation to subjects such as freedom, self-determination and non-discrimination), none of the other conventions addresses autonomy, independence, or inclusion directly, or even uses those terms in their texts. By including these terms and defining them as general principles, the CRPD makes a bold statement regarding their importance to the human rights of persons with disabilities.

General Obligations in the CRPD

Following the Article 3 on General Principles, Article 4 on General Obligations clearly defines the specific actions governments must take to ensure that the rights of persons with disabilities are respected, protected, and fulfilled. Many of the general obligations in the CRPD are common to other human rights conventions. However, the general obligations of States with respect to the rights of persons with disabilities include certain unique requirements that are not mentioned in other human rights instruments. These include such things as promoting universal design for goods and services and undertaking research on accessible technologies and assistive technologies. It is crucial to understand these principles as foundational, overarching obligations that are applicable to every other subject within the CRPD.

One objective of this comprehensive Article 4 on General Obligations is to counteract the historic failure of States to truly understand their obligations to persons with disabilities as fundamental human rights obligations. States have tended to view these responsibilities as representing exceptional treatment or special social measures, not as essential requirements under human rights law. Clearly expressing them as general obligations in the Convention is an important step toward reversing this harmful way of thinking.

Other Cross-Cutting Articles in the CRPD

All human rights are indivisible, interdependent, and interrelated, and all of the articles in

the CRPD are important and relate closely to one another. However, certain articles are

fundamentally cross-cutting and have a broad impact on all other articles. These articles,

sometimes referred to as articles of general application, are therefore placed at the beginning

of the Convention to reinforce their importance. Article 3 on General Principles and Article 4

on General Obligations, discussed above, clearly fall into this category. The other articles of

general application in the CRPD are:

Specific Rights in the CRPD

Articles 10-30 address specific rights, such as the right to work, the right to political participation,

and many others. A full list of the articles of the CRPD is included at the end of this chapter. In

most cases, these topical articles correspond closely to articles found in other human rights

conventions, except that they explain the particular right in the context of disability. A few

articles, however, address subjects unique to the CRPD such as:

Regional Disability Rights Conventions

As of 2007, the only regional institution with a disability-specific convention is the Inter- American Commission on Human Rights, which developed the Inter-American Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities in 1999. However, most regional institutions have adopted optional protocols, treaties that modify another treaty, to existing conventions or have developed non-binding resolutions, recommendations, and/or plans that address disability rights. In some cases, persons with disabilities are specifically mentioned in the general regional human rights instruments.

Key Non-Binding Instruments on Disability

World Programme of Action Concerning Disabled Persons:

The UN declared 1981 as the "International Year of Disabled Persons" (IYDP) with the theme

of full equality and participation of persons with disabilities and a call for plans of action

at the national, regional, and international levels. One important outcome of the IYDP was the

development by the UN of the World Programme of Action Concerning Disabled Persons with

the stated purpose "to promote effective measures for prevention of disability, rehabilitation

and the realization of the goals of 'full participation' of disabled persons in social life and

development and of equality." To provide a timeframe for governments to implement the World

Programme of Action, the UN declared 1983-1992 the United Nations Decade of Disabled

Persons.

UN Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunity for Persons with Disabilities:

Many people believed that the World Programme of Action, although valuable, would not

achieve the results needed to ensure that the rights of disabled persons were respected.

In 1987 the UN convened a meeting to consider drafting a convention on disability rights;

however, at that time there was not enough support to move ahead. In 1990, the UN decided

to develop another kind of instrument that would not be international law but rather a statement

of principles signifying a political and moral commitment to equalizing opportunities for disabled

people. The resulting Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunity for Persons

with Disabilities (Standard Rules), adopted in 1993, was the first international instrument to

recognize that the rights of disabled persons are greatly affected by the legal, political, social,

and physical environment. Although superseded by the CRPD, the Standard Rules are still an

important advocacy tool for the disability community, and many of its principles served as a

basis for drafting that Convention.

The UN Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care (The MI Principles):

These principles were developed in 1991 to establish minimum standards for practice in the

mental health field. The MI Principles have been used as a blueprint for the development of

mental health legislation in many countries. They include some very important concepts, such

as the right to live in the community.

Many advocates in the field of psycho-social disability believe that this instrument establishes lower standards on some issues than is reflected in other human rights law and policy. In particular, there is concern about requirements for "informed consent" for treatment of people with psycho-social disabilities. Disability advocates should look carefully at the standards in this instrument and decide for themselves whether or not it should be used as an advocacy tool for the rights of persons with psycho-social disabilities.

| Exercise 3: Tree of Rights |

| Objective: | To identify how a range of human rights applies to persons with disabilities |

| Time: | 45 minutes |

| Materials: | Tree trunks sketched on large posters 10 cutouts each of branches/leaves/fruits on which to write Chart paper and markers or blackboard and chalk |

| Handouts: | UDHR (short version) CRPD Article 3, General Principles; Article 4, General Obligations |

1. Introduce:

Emphasize that like all human beings, people with disabilities are holders of human rights.

Explain that in order to claim their human rights, people with disabilities must understand what

those rights are and what must be done to respect, protect, and fulfill them.

2. Brainstorm/Construct:

Divide participants into small groups. Provide each group with a large poster size drawing of a

tree trunk and paper cutouts of branches (10), leaves (10), and fruit (10). Explain the exercise:

| Example: | Branch: | Right to Equality before the Law (UDHR Article 7) |

| Leaf: | Right to make decisions about where one lives | |

| Fruit: | Laws to ensure that people with disabilities are not automatically considered "legally incompetent" and are involved in legal decisions that affect them |

3. Report/Analyze:

Post each tree on the wall. Have each group read a few of their branches and the associated

leaves and fruits from its tree.

4. Discuss:

The rights of people with disabilities are not different from the rights of everyone else, but they

do often manifest themselves differently for people with disabilities.

DEFINING AND RESEARCHING DISABILITY

Disability is a complex concept, and as yet there is no definition of disability that has achieved international consensus. Nevertheless, each person involved in advocating for disability rights must be able to explain to others what group of people they are talking about when they refer to persons with disabilities. How you define and express the concept of disability strongly impacts the understanding, attitude, and approach of others toward the human rights of persons with disabilities.

| Exercise 4: Design a National Census Survey for Your Country |

| Objective: | To examine how definitions of disability have a practical impact on advocacy and other efforts |

| Time: | 45 minutes |

| Materials: | Paper and pens/pencils; list of sample definitions |

1. Introduce:

Explain that the purpose of a national census is to count the number of people in a country

and to understand their distribution across different demographic categories. For instance,

governments need to know the number of school-aged children in order to allocate the

necessary resources to educate them.

2. Discuss:

Discuss the following questions either in small groups or the large group:

3. Analyze:

What definition of disability should be used to ensure the most accurate and inclusive

consensus? Below are some examples of definitions or descriptions of disability used in various

international and national contexts.

4. Define/Present/Discuss:

There are many different contexts in which it is important to clarify the meaning of disability.

As an advocate, you should be prepared to express your opinions about what disability means

in various advocacy situations. Work with a partner to develop a definition that you yourself

would use in talking to others about disability rights. Present your definition to the whole

group. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each definition. If possible allow time for

revisions.

5. Research:

Census Questions on Disability

The World Bank has endorsed the following six questions, developed by the Washington Group on Disability, that a government might include in a national census to capture general disability prevalence in a census. Because of a physical, mental or emotional health condition...

|

ATTITUDES AND PERCEPTIONS REGARDING DISABILITY

Although they are entitled to every human right, persons with disabilities often face serious discrimination based on attitudes, perceptions, misunderstandings, and lack of awareness. For example, the misconception that people with disabilities cannot be productive members of the workforce may lead employers to discriminate against job applicants who have disabilities, even if they are perfectly qualified to perform the work. Or it might mean that buildings where jobs are located are not constructed in a way that people with mobility impairments can access them.

Such limitations can affect other population groups as well. For example, in some societies attitudes toward women prohibit them from owning property or participating in public life. Members of racial or ethnic minorities are often forbidden to speak their own language or practice their religion. A person with a disability who also belongs to another group that experiences discrimination (e.g., a disabled woman who belongs to an ethnic minority) may face multiple layers of discrimination and barriers to realizing human rights.

In addition to attitudes and perception coming from external sources, each individual&3039;s attitude directly affects how he or she exercises human rights. A person who believes a disability makes her or him somehow different in respect to human rights will claim - or not claim - those rights very differently.

Destructive Attitudes and Concepts

The Medical Model of Disability:

Perhaps the most significant and widespread myth affecting human rights and disability is the

idea that disability is a medical problem that needs to be solved or an illness that needs to be

"cured." This notion implies that a person with a disability is somehow "broken" or "sick" and

requires fixing or healing. By defining disability as the problem and medical intervention as

the solution, individuals, societies, and governments avoid the responsibility of addressing the

human rights obstacles that exist in the social and physical environment. Instead, they place the

burden on the health profession to address the "problem" in the person with the disability.

The Charity Model of Disability:

Another major misperception is that people with disabilities are helpless and need to be cared

for. It is much easier for people to offer pity and charity than to address the fear or discomfort

they themselves feel when it comes to people with disabilities. It is also often easier to do

something for somebody than to make sure that they have the resources to do it for themselves.

The result of both the medical and charity approach is to strip people with disabilities of the power and responsibility for taking charge of their own lives and asserting their rights on an equal basis with others.

Positive Attitudes and Concepts

Disability as a Natural Part of Human Diversity:

Everyone is different, whether that difference relates to color, gender, ethnicity, size, shape, or

anything else. A disability is no different. It may limit a person's mobility or their ability to hear,

see, taste, or smell. A psycho-social disability or intellectual disability, may affect the way

people think, feel, or process information. Regardless of its characteristics, disability neither

subtracts from nor adds to a person's humanity, value or rights. It is simply a feature of a

person.

Reasonable Accommodation:

A person with disabilities may require a reasonable accommodation, such as a wheelchair

or more time to accomplish a task. A reasonable accommodation is simply a resource or a

measure designed to promote full participation and access and to empower a person to act

on his or her own behalf. This approach is not the same as trying to fix the person or fix the

disability (the Medical Model) or assuming that people with disabilities are incapable of acting

for themselves (the Charity Model).

The Social Model of Disability:

This model focuses on eliminating the barriers created by the social and physical environment

that inhibit the ability of persons with disabilities to exercise their human rights. This includes,

for instance, promoting positive attitudes and perceptions, modifying the built environment,

providing information in accessible formats, interacting with individuals with disabilities

in appropriate ways, and making sure that laws and policies support the exercise of full

participation and non-discrimination.

THE HUMAN RIGHTS APPROACH TO DISABILITY

The social model of disability, which focuses on the responsibility of governments and society to ensure access, inclusion, and participation, sets the stage for the emergence of the Human Rights Approach to Disability, which focuses on the inherent human rights of persons with disabilities. This approach:

The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has summarized the

rights-based approach as follows:

In particular the OHCHR stresses the following ideas:

Barriers to exercising human rights can stem from attitudes, prejudice, a practical issue, a legal obstacle, or a combination of factors. But a disability itself does not affect or limit a person's entitlement to human rights in any way. Defining persons with disabilities first and foremost as rights holders and subjects of human rights law on an equal basis with others is an extremely powerful approach to changing perceptions and attitudes, as well as providing a system for ensuring the human rights of persons with disabilities.

| Exercise 5: Language & Rights |

| Objective: | To understand the role that language can play in supporting both positive and negative attitudes about the role of people with disabilities in society |

| Time: | 45 minutes |

| Materials: | Chart paper and markers or blackboard and chalk |

1. Introduce:

Explain that language may be used in different ways to support both negative and positive

attitudes about disability. This language may be found in the words used for people with

disabilities, the words that describe their disability, or the words used to describe their role in the

family or community. Attitudes may also be reflected in the words that people avoid using.

2. Discuss:

Break into small groups. Ask each group to generate examples of language used in their society

to describe people with disabilities, their disability, or their role in family or community.

3. Report/Analyze:

Ask each group to report their findings. List these terms on chart paper in a table as shown

below. Discuss the following questions:

| LANGUAGE DESCRIBING DISABILITY | ||

| The Person with Disabilities | The Disability | The Role of the Person with Disabilities |

HUMAN RIGHTS ADVOCACY

Every person is entitled to claim her or his human rights and to demand that they be protected, respected, and fulfilled. When you advocate in human rights terms, and use the human rights framework to support your advocacy, no one can challenge that you are asking for special treatment or something undeserved. All stakeholders have a role to play to see that the new Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is fully implemented.

Human Rights.YES! was designed to support you in this effort. This first section has provided a comprehensive study of human rights principles, legal documents, and social attitudes related to disability. By providing detailed information on specific themes related to disability rights, Part 2 seeks to equip disability advocates with the knowledge they need to effect change in both national laws and policies and in the social and cultural environments. Part 3 offers specific training on advocacy strategies and techniques, including defining advocacy objectives, developing advocacy action plans, and measuring your advocacy success.

Just because human rights law exists does not make human rights a reality in people's lives. Positive attitudes and good intentions are not enough either.

Without individual efforts, a firm social and cultural commitment reinforced by group action, and strong implementation and enforcement by governments, human rights cannot be guaranteed!

| ________________ | |

| 1 | See http://hrlibrary.law.umn.edu/instree/b3ccpr.htm |

| 2 | See http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/a_cescr.htm |

| 3 | See Annex 1, page 290 for internet addresses for these documents. |

| 4 | See http://hrlibrary.law.umn.edu/instree/z1afchar.htm |

| 5 | See http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/005.htm |

| 6 | See http://hrlibrary.law.umn.edu/oasinstr/zoas3con.htm |

| 7 | Center for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, Washington Group on Disability Statistics (2007). http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/citygroup.htm |

| 8 | "Draft Guidelines: A Human Rights Approach to Poverty Reduction Strategies" 10 Sept. 2002. UNHCHR Homepage. http://www.unhchr.ch/development/povertyfinal.html |